Deathwhiff 3000 is a four-player cooperative game developed during the summer of 2014 as part of a game design class taught by Heather Kelley, Playing with the Senses, at Concordia University in Montreal. Presented with the challenge to integrate the sense of smell into a playful interaction, a team of artists developed Deathwhiff 3000, a game that integrates a system for scent delivery that associates key odorants with characters in the game. In addition to being the game’s name, the Deathwhiff 3000 is the scent delivery hardware that is at once a virtual and physical device – both the characters in the game and the players in the physical world are connected through the use of the device. In this way, Deathwhiff 3000 pushes the sensory experience of a traditional screen/controller game by relying on the players’ sense of smell in order to differentiate characters in the game.

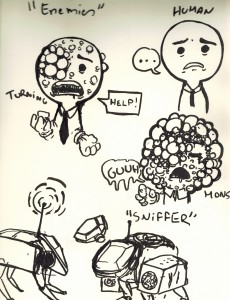

Inspired by Heather’s 2013 lecture The Challenges & Potential of Scent, the team set about to create a game where the use of scent would go beyond that of a stimulus feedback, and operate as an essential component of game play. The concept took many forms during brainstorming sessions all with the goal to use scent as a means to differentiate visually similar characters. The original narrative involved werewolf lore in that scent would be used to identify humans that had been bitten and infected by werewolves. This initial idea evolved into Deathwhiff 3000, a post-apocalyptic game in which an infectious virus transforms victims into zombies. The original concept was maintained insofar as the requirement that the sense of smell be used to differentiate characters in the game, and achieve the game’s objective.

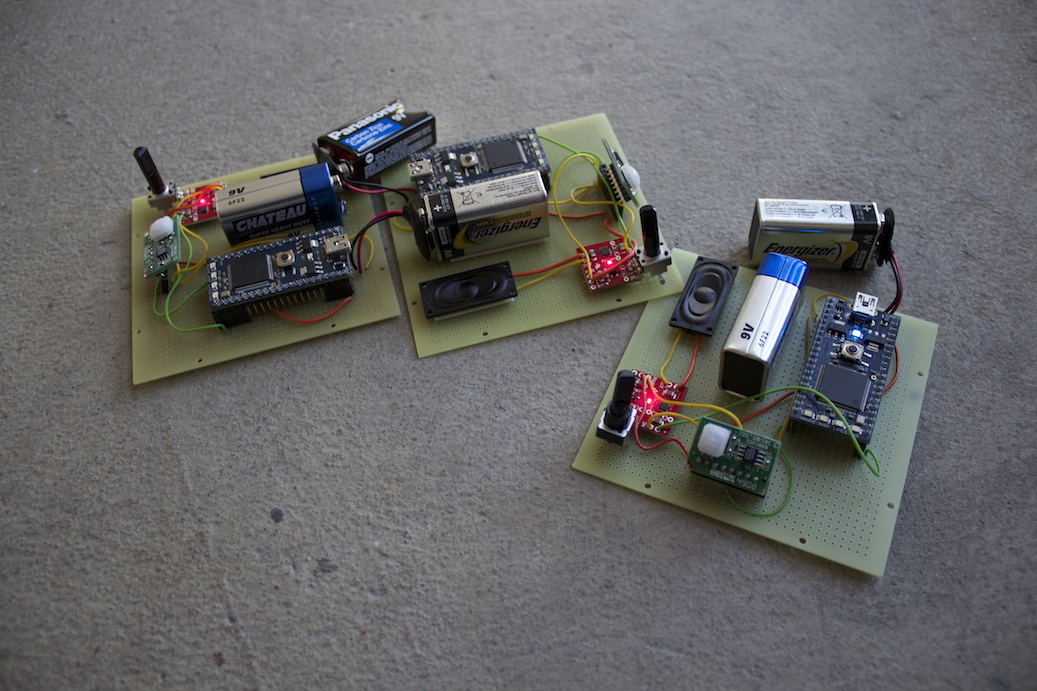

The connection between the characters in the game and the players is through the scent delivery hardware, the Deathwhiff 3000 device. Unable to find a suitable off-the-shelf scent player, the team considered Mint Digital’s 3D printable Olly, a web connected smelly robot. This idea, however, was abandoned due to the Olly’s limited ability to play a single scent. The game’s narrative required at least three distinct smells in addition to a fourth neutralizing odour to facilitate the differentiation between the odorants. For this reason, a decision was taken to design and build a custom scent player that could play four different smells, three corresponding to characters in the game, and one reserved for a neutralizing odour.

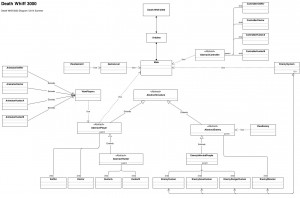

The primary objective in Deathwhiff 3000 is to kill zombies and save humans. To achieve this goal and to encourage team play, the game was designed for four players each with distinct roles – a tech, a medic, and two hunters. The tech controls the Deathwhiff 3000 device and must sniff the human-looking non-player characters (NPC’s) to identify their level of infection. The medic must then either inoculate or vaccinate the NPC’s, and the hunters must kill the incurables and the zombies. As the tech performs the sniffing action, the physical Deathwhiff 3000 omits an odour. It is up to the players to identify the smell and determine if the NPC is either not infected and must be inoculated, infected and may be given an antivirus, or is incurable and must be killed. The medic’s role is to administer the inoculation or antivirus, and the hunters must kill the incurables and zombies. The medic is also able to revive the player characters if they become infected; however, the medic cannot self-heal and must therefore be protected. When the medic dies, the game ends.

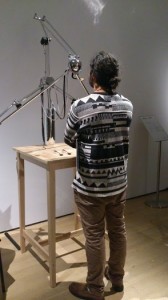

The challenge in designing and building the Deathwhiff 3000 device involved creating hardware that would effectively deliver the odorants to the players without the smells becoming intermingled. Several different designs were sketched out and vetted before arriving at a design that seemed to be the most promising. The final design took the form of a custom-built airtight wooden box containing four small sealed containers for the different odorants. Four squirrel blower fans were mounted on one end of the box and connected to the air input of the sealed scent containers using PVC tubing. The air outputs of the scent containers were then connected to the other end of the wooden box with PVC tubing. All the tubing was sealed with silicon and hose clamps so that each odorant formed a sealed system within the wooden box, each scent with its own air intake and exhaust. Further leak proofing was achieved by installing extra tubing in the box to provide a greater air buffer between the scent containers and the outside of the wooden box.

The selection of different odorants was difficult insofar as finding scents that would effectively represent the NPC’s in the game. As mentioned above, these NPC’s include uninfected humans that must be inoculated, humans that are infected and must be given an antivirus, as well as incurable humans and zombies. A scent was required for each character type as well as one serving to reset the players’ sense of smell. At first, the team endeavoured to use organic smells; however, testing revealed that these types of smells were either ineffective or too offensive. Some examples of odorants that were tested include coffee, fish oil, strong cheese, liquid extracted from rotten vegetables, as well as a variety of essential oils. Through experimentation it was determined that essential oils provided the most convenient form being effective, inoffensive, and easy to work with. This with the exception that coffee beans worked the best as a neutralizing odour. The final selection of odorants for the NPC’s are as follows:

1. For uninfected humans that must be inoculated, Soap & Water essential oil was used to create an impression of health.

2. For infected humans that must be given an antivirus, a mixture of Tea Tree, Eucalyptus, and Vetiver Bourbon essential oils were used to create an odour that combined a hint of the bad smell of Vetiver Bourbon with the more sanitary or medical smells of Tea Tree and Eucalyptus.

3. Finally, for the incurable and zombies that must be killed, Vetiver Bourbon essential oil was used for its distinct and bad smell.

Through play testing, it was determined that the most effective placement of the Deathwhiff hardware was adjacent to the players, and at their chest level while seated. The hardware was integrated into gameplay by creating a game mechanic that pauses the game for four seconds when the tech uses the screen-based device to smell a NPC. During the four-second pause, the Deathwhiff 3000 omits one of the three key odorants, and the players have the opportunity to identify the smell and determine what course of action to take. After the four-second pause, the scent fan shuts off and the fan associated with the neutralizing coffee odorant turns on to reset the players’ sense of smell.

Seeing as the first release of Deathwhiff 3000 had to be completed within a two-week time frame, Processing was selected based on the artists’ skill sets. This was in spite of the fact that the Processing environment is not ideal for coding heavy games. Resultantly, a number of challenges were encountered during the development process. Primarily, these challenges involved the relationship between player actions, collision detection, handling of array lists, handling of animations, as well as memory issues encountered during game optimization. With respect to game optimization, it was unfortunate that much of the artwork for the NPC sprite animations had to be sacrificed in order to preserve an effective gaming experience. In addition to these primary challenges, issues were encountered with respect to both implementing four Playstation 3 controllers as well as effectively calculating scoring throughout the game.

In developing the graphics for Deathwhiff 3000, the two main goals involved creating a cohesive aesthetic as well as developing an approach that enabled the generation of a large amount of assets within a short time frame. Initially, a detailed and whimsical approach was taken with respect to the graphics, a style inspired by the game Castle Crashers. In addition, inspiration came from the game, The Binding of Isaac, insofar as it successfully captures a grotesque aesthetic without being too offensive. This stylistic approach was eventually modified to better mesh with the music composed for the game – the moody nature of the soundtrack called for a grittier aesthetic. Out of all the characters, the medic proved to be the most challenging to design. It was crucial that the graphical representation of the Deathwhiff 3000 device form a conceptual link between the virtual and physical hardware. After some experimentation with sketching a sniffer dog, it was decided that the medic be animated as a human carrying the Deathwhiff 3000 hardware to better fit with the game’s narrative. The second goal to generate a large amount of graphic assets in a short timeframe was necessary to meet the deadline for the games first critique. Within the span of four days, eight sprite sheets of 24 sprites each were generated as well as backgrounds and icons representing various objects in the game. In total, 206 assets were created. Unfortunately, due to the previously mentioned optimization issues, most of the NPC animations had to be cut.

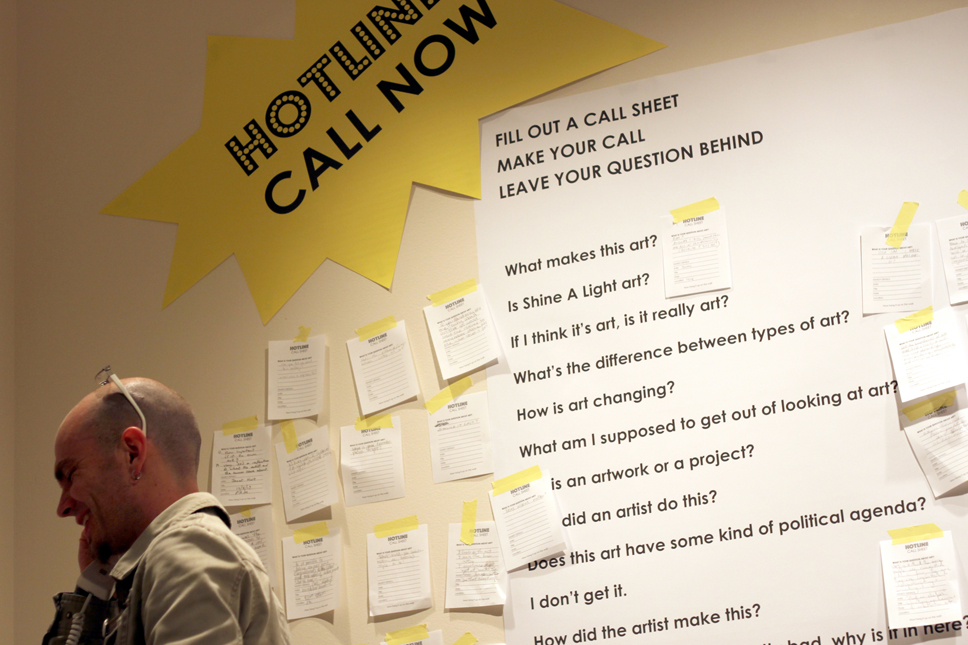

On Monday June 30th the game was presented at Concordia University, and there was an overall positive response to both the concept and implementation. Critical Hit Montreal formed the first team of play-testers, and while they described this initial game as somewhat overwhelming, the second game ran much more smoothly. (In the first play-through no one was too sure as to the mechanics of a scent-based game!) During the second round Heather led the team as the medic, and her trained sense of smell led to much smoother gameplay.

The Critical Hit team was generally impressed with Deathwhiff 3000. They did, however, provide some great comments on how to continue polishing the game. Mainly, it was agreed that a slower-paced tutorial level would be helpful to allow the players to familiarize themselves with the different scents in the game and the core mechanics. It was also suggested that more obvious visual feedback be provided to indicate when a player is attacked and hurt by a zombie. Finally, there were some issues with zombies being generated at a faster pace than the other NPC’s as well as the fact that the game had no concrete win-state. These issues are all being resolved and will be incorporated into a future revision of the game.

Game, Concept & Design by The Deathwhiff Team

Olivier Albaracin Programming

David Clark Physical Computing & Narrative

Milin Li Programming & Graphic Design

Nima Navab Physical Computing & Programming

Ana Tavera Mendoza Animation & Graphic Design

Music byAlexander Westcott

Special thanks to Critical Hit Montreal and TAG for playtesting and reviewing the game.

Deathwhiff 3000 was developed using Processing and Arduino, and its sprites were made using Flash and Photoshop CS6. The Deathwhiff machine was manned with an Arduino UNO board.